Stan Tatkin: What Makes Relationships Work

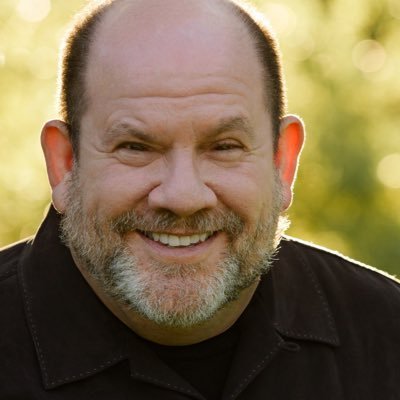

Stan Tatkin is an author, therapist, and researcher who guides couples toward more durable relationships. He developed the Psychobiological Approach to Couples Therapy (PACT), a non-linear approach that explores attachment theory to help couples adopt secure-functioning principles: In short, Stan and his wife, Tracey, train therapists to work through a psychobiological lens. Often, our brains get away from us in conflict—we lose ourselves to our instincts. He has trained thousands of therapists to integrate PACT into their clinical practice, offers intensive counseling sessions, and co-leads couples retreats with his wife.

His latest book,In Each Other's Care, provides practical tools for couples struggling with recurring arguments. In our discussion, he explains how to identify and overcome triggers that lead to conflicts and improve communication to achieve better outcomes. Using the concept of secure functioning, Stan emphasizes the positive impact of healthier arguments. Though his solutions require effort and dedication, they have the power to benefit all aspects of your life. I should know—he has worked with me and Rob before, sessions that were honestly fascinating, for both of us.

TRANSCRIPT:

(Edited slightly for clarity.)

ELISE LOEHEN: I guess I should start by saying I'm relieved I haven't seen you in a minute, it means I'm a testament to your skills as a couple's therapist.

STAN TATKIN: Oh, oh, that's good.

ELISE: Because Rob and I haven't seen you in a while. So, there you go.

STAN: How is Rob?

ELISE: He is great, he's good. It's funny, as I was going through my notes, cause I read your book a while ago to blurb it and then I was sending him things and I'm like, we need to be careful of this and I'm reminding you about this. And he's like, what are you doing? I was like, I'm preparing to talk to Stan. And he was like, oh, okay. Our thing is, which maybe we'll get to is like the parallel play as you know, and then how that can lead to real loneliness because you are so comfortable in your own world that being alone together can actually feel more lonely.

STAN: Yeah, it can. Tracy and I started doing a little bit too much parallel play as of recently, and I started to complain.

ELISE: Yeah.

STAN: There's something about being together but not interacting over time, if you do that a lot, then at least one person starts to feel a little lonely.

ELISE: Yeah. No, and I think you wrote it beautifully. You said, “Nothing is wrong or bad about parallel play unless it becomes the couple's main diet. And being alone can make one lonely, but being alone with someone for extended and repeated periods is a particular kind of loneliness. It's a kind of lonely that harkens back to many childhoods in which parents or caregivers were physically present, yet unavailable for engagement.” Ooh, Stan.

STAN: I know, I get a lot of people who will say, and it usually is a red flag for me, that my, my mother was home all the time. She was always there. But then when I ask how much engagement there was, there's very little, in memory, in autobiographical memory. And so then I have an idea, the same thing by the way with parents that have, and I did a little bit of that during Covid. You know, I have a home office, and the doors closed because you're working. And it's difficult I think for people in home to fathom after a while how you're there, but not available.

ELISE: Yes, that's so true. I mean, I remember, just for context, for people who are listening, working with Stan is a really interesting experience, not only because it’s a bootcamp, you're not breathing dependency, but at the beginning when you take people through that series of questions along the lines of “did your parents enter your world or did you enter theirs” and "what happened when you were sick?” And you really get at some of that presence, yet absence. That is so common I think, for so many people.

STAN: Well, it's a different kind of history taking, people think it's about being loved and it's not. In the attachment world, there's a feeling of being loved, but that's not necessarily what it is. It’s engagement. It's around feeling safe and secure in the world. And one of the ways that we feel safe and secure in the world is by having at least one person that we can depend on and, you know, and vice versa. We know that is a fact when it comes to happiness and longevity and health. By the way, when you mentioned bootcamp, I have long wanted to set up a bootcamp for couples, intransigent couples, you know, that are not doing well, even in couples therapy, something, you know, that forces them to work as a team, like life and death.

ELISE: Survivor couple. Yeah. That's actually a great idea, I don't know if that TV show exists, but I think you should pitch it.

STAN: No, there isn't. But, this is, to be serious, this would've been a research project to see if we could turn couples that were not working out in treatment, would that actually work, to get them to work as a team, as an alliance. And I have a suspicion at would.

ELISE: Yeah, it's so interesting because the other, and we'll get into attachment theory in general, but the other really fascinating and yet, frustrating part of working with you in therapy, Stan, is that we all come, right? Like I'm sure people can relate to this, you come with your list of grievances and the quote unquote content of your lives and the events in which your partner disappointed you or failed you or disavowed you in some way and you could not be less interested in the content. In fact, I feel like you repeatedly have been like, this is so boring. Like, can we move on? Like, you're looking at the underlying interaction, right? Can you talk about that? Like the culprit, the interaction as culprit rather than what we layer on top of it.

STAN: What I've found through my own research is that, and you know, for years I've studied couples with digital video using frame analysis, to study faces, bodies, movements, and voices. And what I have found is that there are two main things that will crash a relationship over the long run. One is a lack of organization and structure, as co-created by partners. And the other is the manner in which they interact when under stress, it's never the topic. The topic is the stressor. What repeats is the manner in which they interact when one or both of them is in stress or distress and that is remarkable I think.

ELISE: Yeah. And you write: “How complaints become conflict should interest everyone s since the point of this book isn't really complaints, subject matters, or areas of importance.” I think where we always get stuck rather than understanding like the unstated need or what's actually happening in the room that triggers us into this perennial conflict. You mentioned structure. What is that? Is that like all of the things that we don't state because we don't even recognize how we want tasks to be divided or for this alliance to work? What is that?

STAN: I find that it's only the couple that enters into a union of free adults, right, equals that come together without any kind of co-created architecture or structure or rules of engagement, they fly by the seat of their pants. And no other organization or alliance or team, a rock and roll band, a dance troupe, you know, a business, would never assemble to get people on board without without a shared purpose, a shared vision for what we're gonna do and what we're not gonna do, and shared ideas of how we're gonna govern each other to keep each other from hurting each other or hurting the union, hurting the organization. And yet, couples don't do this. There's a different set of entitlements and expectations, most of them unstated that goes on in the love relationship. And yet it's really important that partners shape this culture, this new culture that they're creating. But alas, that's not what people normally do, and they suffer because of it.

ELISE: Why do you think it's unstated? Do you think it's because we're not even conscious or aware of what it is that we want a relationship to be? Or that we're governed by how our family of origin functioned? Is it that we haven't thought about it or are we ashamed to say it? Or what is it?

STAN: I think we’re, as creatures, and this is true of every living thing, we, you know, we operate, according to the principle of energy conservation. That's nature. That means that if we can, we do the least amount necessary, that's the whole idea of automation, that most of our lives are operating automatically, based on memory. That’s called procedural memory. These are the things we do day in and day out, and we operate by pattern recognition, which is memory. But it's a memory that goes unchecked by critical thinking. And so we go about our day, basically not thinking most of the time, I'd say upwards to, you know, 95, 99% of the day can be completely automatic and very little of that time is energy expending thinking, critical thinking.

So, I think it's too much work. I don't think people think they should have to do that. And I think what happens naturally is nature always repeats itself. And so how many people care to go back to their childhood and examine it? How many people care to keep in mind the things they don't want to have in their current adult relationship that they just took for granted or didn't question in their family of origin? I'd say that's everybody. I think the only people that really do take a look are people who suffer, that's the only thing that creates that looking inside and looking backward and to try to get a sense of oneself. Most everybody's just doing what they know and what they've experienced, and that's as fancy as we get.

ELISE: Yeah, I think that makes so much sense. And I think, you know, culture is strong with us, right? And it's contagious. And so much of our culture is storytelling around these things too. The fairy tales, the marriages that we see on TV or in movies, in romantic comedies, and there’s obviously a disconnect. I think so many there's this like rolling ball of eventuality or inevitability that many of us think that we're part of. Right? We'll meet someone, we'll get married, we’ll have children, we'll die. And that somehow you're in a river that will bend its way through your life regardless of whether you steer. And that it should be easy, that that if it's not, that something's wrong, and even if that's disconnected from the reality of your own life, right. Somehow it's like, I don't know whether it's painful to examine our stories or I don't know what that is, but how many couples or families are functioning optimally anyway? Zero?

STAN: Well, you'd have to define what optimal is. I mean, that's why I don't like words like normal or healthy, you know, who's to say what is normal and healthy? I'd rather think in terms of how well do people work together? Do they work together in a manner that is collaborative and cooperative? Or do they work in a manner that accrues resentment and threat? You know, the threat, the kind of threat I'm talking about is memory of being hurt, the way one makes a face or the tone of their voice or the word choices they use. And, you know, I think what you were talking about speaks more to our naivety about how human primates actually operate, we aren’t easy animals, there is no person who is easy. They may be easy to one person and not to another, and they may be easy at times, but they're not gonna be easy all the time. There is nobody who is, maybe someone who's on life support in a coma, but that's about it.

If you're a human primate, you're difficult. You’re disappointing. You’re irritating, right? You get in my way, you misunderstand me. You step in my toes. You're not on the same page often, these are just the way things are. And so the only way that we have to protect ourselves from each other is to create principles of how we're going to govern. You know, what we're going to do and what we're not gonna do. That's the basis of civilization, it doesn't end religion and the law understands human primates are not trustworthy.

ELISE: Let's talk about the shared vision, shared purpose and some of those rules, before we get there, I wanna talk a little bit, you mentioned it, how you put people on video, you've done this to me, and then you watch us re-react and you see Rob's chin go up and his arms cross and I'm still talking and explaining and then when it's played back, you're like, why are you still talking?And it's a really interesting experience and people can imagine what it's like to see yourself in an escalation of conflict. And to see the way that we read each other, because the more Rob lifts his chin at me and shows defiance, the more I feel compelled to explain myself. And you get into these cycles of micro communications, I think you call them. And we do this, too, in the absence of seeing what we want on our partner's face, like interest in what we're sharing. Right? So can you talk a little bit about the way that we are communicating without recognizing that we're communicating, and then how that makes us go sideways?

STAN: One thing my work has taught me is how human interaction is a comedy of errors. People are making so many errors without knowing it. I think I'm making sense to you, but I'm not. I think I'm being clear, but I'm not. I think I understand you, but I don’t. I think I heard you, but I didn’t. I think when you raise your chin, you're looking at me defiantly or someone else, arrogantly or someone else, like you know, looking down at your nose. But maybe you don't think that, you're just lifting your chin because you naturally do it. Lifting of the chin, by the way, is a skeletal feature of when our heart rates go up and we start moving towards higher arousal, we'll elongate our neck and our back and we'll lift the chin sometimes. So often means nothing but optically, to the other person, it doesn't look so good. Just like looking at scans doesn't look so good, or, you know, looking away for too long, or staring too much. All of these things are subjective and for one person, it doesn't bother them, for another person, it drives them crazy. So it's a comedy of errors. The more I understand, the more I just see this as the human condition. I even wonder about pathology now, what we consider pathology and how much of that really is an amplified effect of being human. And so you start to see how hard we are on ourselves and how hard we are on each other. When most of the time we're not really doing anything on purpose, we're doing it automatically or reflexively. Here's another example. I don't know my face is looking angry. I thought of something that made me angry, had nothing to do with you, but the mirroring response is a matching response, which is a human empathic response, causes you to look angry, and now I accuse you of being angry. I have no idea that I started it. I wouldn't have an idea of that, but that's the kind of stuff that I observe.

ELISE: Yeah. And then people fall into these old tropes and then you sort of running yourself into, for me it's this, Rob doesn't care and doesn't pay attention to me. And Rob is like, Elise thinks I'm an idiot and is always lecturing me like I'm one of her children. And that's this silly loop. It's a silly loop and obviously it's not at all aligned with either of our intentions, but this is what plays out. He feels like I'm chastising him as a child and I think he just doesn't understand me.

STAN: This is everybody.

ELISE: Yeah.

STAN: That's why the idea of relationship should be easy is nonsense. We make it easy by creating an organization based on the fact that you and I are different and will always be different, but we're smart enough to look where we are the same and where we agree. Our tendency is to always look where we disagree and where we are different, and that is an error of collaboration or consensus making.

ELISE: Right. Whereas I think so many of us are also trained to fix the problem, quote unquote, right? That the content is the meat of it. So if I can just get him to agree with me on this thing, and meanwhile, your point is admit the debacle, apologize, and scramble to find ways to prevent that event from recurring. Like, we'll never solve all of our problems in that way. Right?

STAN: The way to solve problems, if you have a problem in secure functioning, which is the only thing I sell, in secure functioning, if you have a problem, I have one. Therefore, we should take the problem and work on it as a third thing, like a puzzle. But most people don't do that. They work on each other, which is war. So as soon as I start working on you, or at least you feel I am, it compels you to do the same. And now we're in a tar pit. Now we can't get out and we can't get anything done because we're compelling each other to protect our own interests. And that drives us into a one person system of me, my, I, and you, you, you. That's an error. Right? That's a common error among people, when we should be working dispassionately on solving the problem as quickly as we can, and then take it off the table for now and go have lunch. That would be the way to work.

ELISE: Yes. That hits. Can you give an example of. Something that's a problem that could be solved like a puzzle rather than something that needs to be fixed in the other person. Can you give a concrete example?

STAN: Let’s say I have a problem with you swearing, it bothers me. It doesn't bother you from where you come from. It's not a problem. So I'm not gonna get consensus with you simply by saying, if you want to make me happy, don't swear. I don't think that's a very good selling point. And it's also accusatory. There's something wrong with you and there's something better with me. But I'm gonna look to where we would agree. Do we both want to talk to each other and feel comfortable and feel ease with our talk? Cause we have so many on our plate, we're spinning so many things to do. Would you like that? Do you think we should do that? You would probably say yes. Okay, so why don't we take off the table things that disturb that comfort, things that interrupt. One for me is swear words, but I know you have things that I do that also, uh, irritate you and interrupt discourse when we talk and I get excited in a way that really bugs you. Why don't we put things in place to stop each other when that happens so we can continue our conversation and not get sidetracked? What do you think?

ELISE: Hmm. Yeah.

STAN: You know, it's gonna go back and forth, but if I do this thing that, that interrupts you or that irritates you and that takes you off course, I'm giving you permission to remind me, cue me, confront me on it, and I promise I will yield, I will cooperate immediately without pushback.

ELISE: Yeah, and I think this was in maybe our first ever conversation, but this one very much relates to my marriage, which is that Rob has a fair amount of social anxiety. He'd rather just stay home even though he ends up enjoying himself more than he thinks he will. Whereas I can come alive in a social event and you write about forming an agreement with Tracy, cause you are the Rob in the situation where you predetermine when you guys will go home and you have permission to go sit in the car and pretend to be on a work call while you're watching YouTube or whatever.

STAN: There's an acronym that one of m colleagues came up with Pepper, p e p p e r, and what that stands for is: predict, prepare, and plan for what could possibly go wrong, and revise the Rs, revise as necessary or repair if we make a mistake. So before we go into anything, we tend to predict what could disturb our good time, because for us, our relationship, we decided comes first before anybody and everything. Therefore, we have to guarantee our good time, our safety and security first, and then we consider other people. So that's part of our planning. And then we predict what could get in the way, including each other. So the story about the party is more about bargaining than anything else. I don't wanna go to this party and Tracy wants me to go with her. Well she has to sell me, she has to bargain with me. Why? Because we wanna be together, but she doesn't want me complaining. She can't afford me to feel resentful. So, we agree we're going to make it good for both of us before making any move that goes in both directions.

And so I may say, okay, I'll go with you, but I wanna watch a movie when we get home. Cause I love watching movies and she hates them. And see if she'll take that deal. Right? When we get there, there are some people that I get really uncomfortable with, let’s say, why don't you stick by me tonight? If you stick by me? And if we leave, if I need to leave, let's say around nine, can I whisper in your ear and will you cooperate? Yes. I may not wanna leave. Right. So, all of this is pre-thought of so that there's no looking back and litigating something that either of us feel resentful about. That's the whole idea.

ELISE: Mm. It's very helpful when we remember to do it, and this idea, like ensuring, regardless of the family of origin, that the relationship is the primary thing. It's very difficult, right, when you have kids or other factors in your life. But is that true even in the presence of kids that if the partnership isn't the primary thing, everything else will suffer?

STAN: I've thought of it every which way, and people, of course can be secure functioning if they as long as they agree on what's the highest priority. Right? It's not what I think, but it's what they think. They just have to agree and know what they're agreeing to. I prefer and think the best thing is to put the couple relationship first because, in terms of leadership, the couple is I see as the top of the food chain. They are in charge of everyone and everything. If they are considered, you know, co-equals shared power in authority, then it makes sense from a decision making situation, a hierarchical situation, that if the couple is in distress or isn't functioning well, are the kids going to be okay? Probably not. We know that that affects children. Will creativity and job performance be affected? Yes. Everything will be affected, including health. So every which way, you know, we can think of it logically, it makes sense to put the center of the universe, set the center of the universe as the couple system, because they're the time travelers that are moving through time. There has to be a kind of a sense of feely and dedication as a part of, of their feeling safe and secure, otherwise, there'll be trouble at the top. So it's a practical, tactical idea. It doesn't mean kids are left to fend for themselves. Not at all.

ELISE: Right, since we glossed over it, cause it's obviously foundational to your work, but not the primary focus of this book, but can you quickly just say the difference between secure functioning and insecure functioning.

STAN: Secure functioning is different than secure attachment or insecure attachment. Secure functioning is basically based on social contract theory of fairness and justice. So here we're talking about adding sensitivities. So that's an attachment value. So a secure functioning couple is a couple of equals in a symmetric relationship, two generals, two executives, two bosses that have to work together cooperatively and collaboratively at all times or they will fight. They have to be mindful of that. They are attached in an interdependent way. Everything I do will affect you, and if it affects you, it's going to affect me in return. Therefore, I have to consider you at the same time I'm considering myself. That's a two-person psychology construct. Now we know that that is what people do in the armed forces and special forces, cop car partners, dance troops, people that are interdependent because they all want the same thing, or they have the same purpose, and that is to stay alive, whatever it is, that's the great leveler. That's the great thing that makes different people the same. We're in it for the same reason and we want the same things.

That's secure functioning. Very simple, but really hard to do because of our species, because of the nature of our species, which is to be xenophobic, in other words, to otherwise be selfish and self-centered, to be impulsive and moody and fickle and opportunistic. These are all the features of the human primate for real, along with all the beautiful, wonderful things. But the off the line factory, human primate can do a lot of damage. Take your two-year-old and imagine giving your two-year-old all the rights of an adult in an AR 15. You should be very scared, alright? We're only a little ways from that as adults. So, therefore, we have to operate in this manner. Otherwise we will confuse each other too often as adversaries when we have to be allies. So, insecure functioning is one person thinking I do it because I felt like it. I made the decision cause I wanted to, it’s good to be king.

ELISE: Yes. Like, I'm gonna go play golf all day on Saturday without discussion or any consideration for what that might mean for you. That like a secure functioning relationship, that's a conversation where you're bargaining and figuring out.

STAN: Or I withhold information that you should know. That's one of the most common ones.

ELISE: That's the basis of betrayal. Right?

STAN: Yes because discovery of information that I believe I should have known but was left out of constitutes in my mind, betrayal, and the degree to which that information was really vital is the degree to which I could experience PTSD. It's a major, major, treasonous experience.

ELISE: Got it. That would be an extreme version of an insecure functioning relationship, and that obviously is like infidelity or massive breaks in trust and or consideration.

STAN: Right. All of those things happen systemically. They don't just happen out of nowhere. When people lie or cheat. It's not simply that there's something structurally that was never built, like they're like people are flying a half-built plane, right? Which is dangerous. And so we could predict that if we met those people in the beginning, we could predict, based on how they structure organized their relationship, whether this would be possible or not.

ELISE: Do you think that that's because if we followed the tenants, which we can get to now about these purpose centered agreements and these shared values and shared purpose, that someone inclined toward infidelity might be resistant to that idea of like a co-equal, co-valued relationship, or how would you see that in the early part of structuring or organizing a relationship?

STAN: In secure functioning relationships, it's harder to lie and cheat. Because there's an understanding that there must be free flow of information. The left and right hand have to know the same thing. Otherwise, they can't function as a team. They have to have this information. It’s actually one of the greatest commodities, is information. And so it would be very hard for that to happen if that was a functional agreement, a principle, a value, a moral, principally held value by each individual. It would be much harder to do cause it would require a whole lot of things that violate secure functioning principles. There would be resistance, but there would also be something that would be a betrayal of self because principles should be based on a selfish. Moral value of good for me, it also must be good for you. But it starts with, it has to be good for me, otherwise I won't do it when I at least want to.

So basically, basically couples are building structures that, based on agreement of what the best thing we could do at any given point or the right thing, we could do, even though it will be the hardest to do. That's a good life, a purpose centered life, not feeling centered when it comes to structure and organization, right? These things are there to protect us from each other.

ELISE: Got it. And is that excavation and articulation enough in of itself to be kind of protective? Or is it in that process that you start to see, you could call them red flags, or someone being like, I don't actually feel like I would wanna ever tell you everything, or like, I don't agree with this.

STAN: People may not agree, and often don't. One person says, I don't believe in full transparency, and here's why. They're not wrong. The other person, I believe in full transparency and here's why, they're not wrong, but if they can't get each other on board with one or the other's idea or principle, that's called a deal breaker, they won't be able to do business.

ELISE: Right. And you talk a little bit, I mean, you don't get into the, the weeds around polyamory, but you say, and for the purposes of someone who would be inclined to want multiple partners, that's the structure you have to establish in order for that. So that's functional as long as it's within the functioning parameters of your shared agreement.

STAN: Again, we're adults. Secure functioning is only determined by a partner's ability to speak for themselves, to opt out honestly, to represent their needs and wants accurately and honestly, and be able to find where they agree and where they disagree. Some of the errors of disagreement, like polyamory, one person may say yes, but they are not on board, and that's going to cause problems because they simply don't wanna lose their partner. That's going to create downstream effects that are gonna be disastrous. So it's basically becoming an adult. It's growing up and being responsible. You know working together to create the moral structure of the relationship, which by the way, doesn't exist except in our heads. It's, there is no relationship, it's an abstraction. It's so we, you, and I have to make sure that our heads agree, our fantasies about, or a mythology about this relationship has to be the same, or we're gonna get into trouble.

ELISE: Hmm. God, it's so basic and simple, and yet it's a step that so many of us skip, right? Or you think that it's like these cultural ideas and as we see speaking in polyamory, like there actually is no single way to have a relationship, and it's a highly individual process. Even as so many of these seem like cultural values for all of us.They're not, right?

STAN: There's several different ways of describing culture. One is the large system culture of one's country or ethnicity or religion, but there's also the culture of the family system. So you could be neighbors, but you're still coming from two different cultures, family cultures, and we know on an attachment level that's kind of like a culture, in the family culture, is the relationship the all important thing? Is it the center of the universe, or is the self? In most families it's going to be the self, which, you know, has its problems. But they're different cultures and it informs how we do things, how we act, how we move toward and away from others. And, so the bottom line is, we pick, we pair bond by recognition and familiarity, but that doesn't mean that we're the same. That means that in big areas we recognize each other and we're not that far away from home. Otherwise, if that person was too stranger ish, we'd get homesick. Right. So, and if they're too familiar, then it would feel like family too much. So there's this mixture, right? But we're definitely different. And that's gonna come into visual clarity when we live together.

ELISE: Right. Yes.

STAN: It's a big shock to the system. But differences has never stopped people from creating alliances and teams and unions. It's never, never stopped us.

ELISE: Right. So you talk about these shared principles of governance, which I love these. These are some that you suggest as you get started, like “we have each other's backs at all times. Without exception, we repair, correct fix or make amends without explanation, condition, excuse, etc. We protect each other's interests and public and private at all times.” And you have this list, you sort of start with six, but do you think that these seem quite universal. To me, right.

STAN: Yeah, most people probably would want them, but you'd be surprised. You'd be surprised. There are a lot of people who do not believe in this, for instance, we don't leak information without each other's permission leak information. I don't talk about you to my friends. I don't tell things that you don't want other people to know. I don't complain about you to my family. You don't do that. But there's some people who are embedded in a culture where that's exactly what they have always done, and they're gonna continue to do it. They don't think anything's wrong with that.

ELISE: Right.

STAN: And one can respect that. But will it work with someone who doesn’t agree? It won't. No. So we can disagree. We just may not be able to be together.

ELISE: Right. Got it. No, that makes sense. Let's switch gears and just talk a little bit. Cause I thought this section was really interesting where you talk about entitlement because of mistreatment in childhood and how we try to. Consciously or unconsciously, we will all set out to settle these scores as we hold others accountable for the sins of our caregivers. I thought that was really interesting because it also shows up culturally, right? And we're, it's like, how do you help people? And this seems to be something that as Americans we're, we're contending with, people are contending with this all around the world. How do you help couples? Acknowledge what they didn't have or what happened. And then, I don't wanna say move on because that's dismissive of people's pain, but how do you break couples out of this cycle of constantly wanting to be, I don't know, validated or like rewarded. I don't know what it is, right. But it's something that we all get stuck in. How do you help people with that?

STAN: The great family systems thinker, Ivan Boszormenyi-Nagy, made an impression on me many years ago. He was one of the early family systems pioneers who put fairness and justice in motion and suggested that family systems, that function in a way that's too unfair or too unjust with the kids, create kids that are going to, he calls it a revolving ledger. I keep track of all the injustices, I will make society pay for that, and that's again human nature. It carries over in memory. So if I got a raw deal, but I never grieved it, I'm still angry, I'm probably still connected to that relationship in some way. I haven't disconnected from it. I'd have to grieve it in order to do that, and so I'm stuck in the past. The best way to deal with the past is to go into the future and co-create something that's better. That's the only way to settle that score. It's not to make people pay for what they did, but it's to put things in place so that never happens again, so that we have, you and I have a home that is far and away better than the home we had, and we're constantly shaping it better, better, better to best to ultimately awesome.

We can do that. But if you are stuck on and litigating the past, you can't move forward. And we can't move forward. And you cannot get rid of, or you don't, we don't get rid of memory but we relegate memory to, you know, in terms of neuroscience, to dirt roads because our present and future experience is so different that we start to separate from that memory and that's good life. So it is, again, a mistake not understanding how memory works to stay in the past and to try to litigate what happened. Instead of learning.

ELISE: And as part of that, you know, you mentioned grief and I feel like so many of us sort of skate on top of these lakes of grief and is part of it figuring out how to tap into that anger so that you can access the grief and let it come up so you can feel it. Is that a necessary part of healing and repair?

STAN: So I think of the past as always present. You don't have to look in the past, the past will look for you in the present. Something will happen that reminds you. You’re being asked to do something different than you've done in the past. You are taking care of your kids in a way that no one ever took care of you. That's a really good example. I'm going to start grieving or I'll hate you. I'll feel envious of you. Right? How come you get away and parents do feel envious. How, how does my kid get away with things that I never got away with? Right? That makes me mad. It's as if I can't see these children as new and something different in context and time. I'm comparing it and contrasting it to the deprivation of my own childhood, and then it makes me angry. But that's not grieving. That's not accepting that I lost something. Anger keeps the connection alive. Grief is what allows us to separate and still not get rid of that person in our head.

We can't get rid of those people. We just have to make peace with them and realize that that ship sailed. And I didn't get those things. I was treated unfairly. I was abused, that happened. Do I want to live that life going forward? No, I don't. So I'm gonna have to create something with my partner that is far and away the thing I want and that I didn't have, and that'll remind me of my anger. So that's why I see the past is always present. Move into the future, and you'll be confronted with your past every time. You don't have to go looking for it.

ELISE: That's really powerful. And our lack of access, culturally, to grief or to sadness, it’s funny, I have a book coming out next month—

STAN: Congratulations. I heard about it. Yay.

ELISE: But it's about the seven sins as a construct for women and goodness. Originally there was an eighth sin, sadness, and I included it in the book because. I feel like an aversion for sadness is lodged primarily, I think, in the minds of men. And this disconnection from our feelings, our inability to properly cycle and process. And how damaging, culturally, I think, how damaging it is for all of us when that un-metabolized, unprocessed rage isn't transmuted and shaped, but it's hard. It's really hard.

STAN: Also, worse, too because we're more distracted today than ever in our life on the planet. We have so many ways of getting away from space and silence, that we can defer, defer, defer, until, you know, everything comes crashing down. Whereas there was much more space to be with our thoughts, to contemplate, to meditate, to be with nature, to be able to think. And so there are a lot of things that are different today than used to be. And so that's another reason why people can avoid grief and depression, by being manic.

ELISE: Yes. And busy. I know this well, if you just keep going, you don't have to feel. I can be in this boat, you write: “Distancing partners commonly set up shop by admiring their own independence.”

STAN: There's distancing, in the attachment world, also in the personality world, it kind of fits if we group people, in either the distancing group, meaning that their main defense, against threat is to distance, or the clinging group, their main defense against interpersonal threat is to clinging. And then there are people who are not afraid of abandonment nor being engulfed. They're not so afraid that they have to develop these defenses, and we would think of them as secure. Right. Secure or psycho neurotic. It doesn't sound, that doesn't sound very midline, psycho neurotic, who wants to be that?But, actually in the personality world, that's considered normal. Woody Allen says, you know, the miserable, not the horrible, right? That's, you're just miserable.

ELISE: In your experience, and do we all follow along some spectrum? Do people exhibit typically signs of both or is it you're really one thing in the world of attachment or you have one instinct?

STAN: In research and in treatment, we're only concerned with people who are stuck and rigid in one area, like a one trick pony. I'm always reactive to anything that, to me, looks like withdrawal, rejection, abandonment or punishment. And then I react, right? And I'm too acutely picked up by sensory inputs and it's like a relational trauma. It makes me difficult to deal with up close, because my way of protecting myself is threatening to you. Or I'm constantly bothered by your neediness, your proximity. Your wanting to hold contact with me. I feel engulfed. I feel interfered with, interrupted. Like, you know, it's all about you. I'm needed. I'm not wanted, I'm a tool, right? And I feel that way all the time. And that makes me very difficult to be with, right? I'm protecting myself, but at your cost, it's threatening to you. I'm conflict avoidant, all these things.

And then, the center area which we would deem secure is, you know, everything. Because these are all human qualities. So in our relationship, there are times when I'm more clingy and that that makes you distance a bit. There are times when I'm more distant and it makes you clingy a bit, but it's fluid and it's a phenomenology that happens inter subjectively between two people, and it's more systemic than fixed.

ELISE: that makes a lot of sense because I can recognize in myself, I'm sure anyone listening can, the moments when I choose to distance versus the moments I rush in to try to overcompensate.

STAN: Right. Tracy will not distance purposely, but she'll just be more in involved in other things, and I become, you know, a clingy little baby. I go back to my island, that’s in my second book, on my island of avoidance.

ELISE: Right. Island, waves, and anchors.

STAN:Yes, right.

ELISE: It's funny cause I was like, I am an anchor and one of my former coworkers was like, “you're an island, but it's nice that you think that about yourself.”

Well, it's always wonderful to see you. Hopefully we can just keep talking like that. This, and not in therapy. Although I do love sessions with you and Rob does too, because they're fascinating. You learn a lot about yourself.

STAN: It's so interesting. People are fascinating.

ELISE: And I always say that about you when I recommend you to people that one, you can't get engulfed in therapy with you because you're very like, I'll see you a couple times and then work it out. But also, I'm like, you'll learn so much about yourself that it's fun. Even if it's hard.

STAN: It's hard. It's hard for me too. We have to walk the talk. It's hard to do the right thing when it's the hardest thing to do. But it feels so good when you do it though.

ELISE: It's true. It's true. You're the best. Thank you so much.

I love Stan, he is brilliant, and has taught me so much about myself through the prism of attachment theory. He’s written many, many books, and this one, In Each Other’s Care, certainly builds on the others, but you don’t necessarily need to have a deep understanding of attachment theory and secure functioning to get a lot out of it. The basic thesis, he writes: “My premise in this book is that unskilled interactions repeated and unrepaired during stressful moments are a principal cause of mutual dysregulation, dissatisfaction, threat inflammation, resentment, and avoidance in all relationships. How complaints become conflicts should interest everyone since the point of this book isn’t really complaints, subject matters, or areas of importance. I have come to recognize—over many years of studying my own and other relationships—that microaggressions expressed and perceived during stressful interpersonal interactions are a leading cause of coregulatory dysfunction in couples and eventual relationship dissolution. Poor interactions, therefore, are a central culprit.” And it is honestly so relieving, as much as you, again, want to air grievances and be confirmed in all of your frustrations, that really, who cares? Stan is the first person to say, “this isn’t interesting, are you guys done yet?” Because what is interesting is what is always underneath: those unmet needs, unstated expectations, what you want from your partner, and what’s being devalued, denied, or overlooked—not out of malice, is his point, and not out of a lack of love, but just because we’re terrible communicators. So, I love Stan, I love his work and if this is resonant, you will find value in everything he’s put into the world. Okay, I’ll see you next week.